I should preface what follows by telling you that I haven’t taken any other courses on the subject of teaching. For all I know, there’s nothing new here. That said, I have never experienced a course like Greg Wilson’s, so either the methods he promotes are not widely known, or they’re widely ignored, or I’ve been really unlucky.

The easiest way to get Greg Wilson’s wisdom is probably to read his book-slash-website, Teaching Tech Together. (It’s free, but you can get a hard copy if you prefer.) It’s really good. You can get the vibe — and much of the most important advice — from the ten Teaching Tech Together rules laid out on the main page of that site (box, right).

As you can probably tell, most of it is about parking your ego, plus most of your knowledge (for now), and orientating everything — every single thing — around the learner.

If you want to go deeper, I also recommend reading the excellent, if rather academic, How Learning Works, by Susan Ambrose (Northeastern University) and others. It’s strongly research-driven, and contains a lot of great advice. In particular, it does a great job of listing the factors that motivate students to learn (and those that demotivate them), and spelling out the various ways in which students acquire mastery of a subject.

How to practice

It goes without saying that you’ll need to teach. A lot. Not surprisingly, we find we get much better if we teach several courses in a short period. If you’re diligent, take a lot of notes and study them before the next class, maybe it’s okay if a few weeks or months go by. But I highly doubt you can teach once or twice a year and get good at it.

Something it took us a while to get comfortable with is what Evan calls ‘mistaking’. If you’re a master coder, you might not make too many mistakes (but your expertise means you will have other problems). If you’re not a master (join the club), you will make a lot of mistakes. Embracing everything as a learning opportunity is less awkward for you, and for the students — dealing with mistakes is a core competency for all programmers.

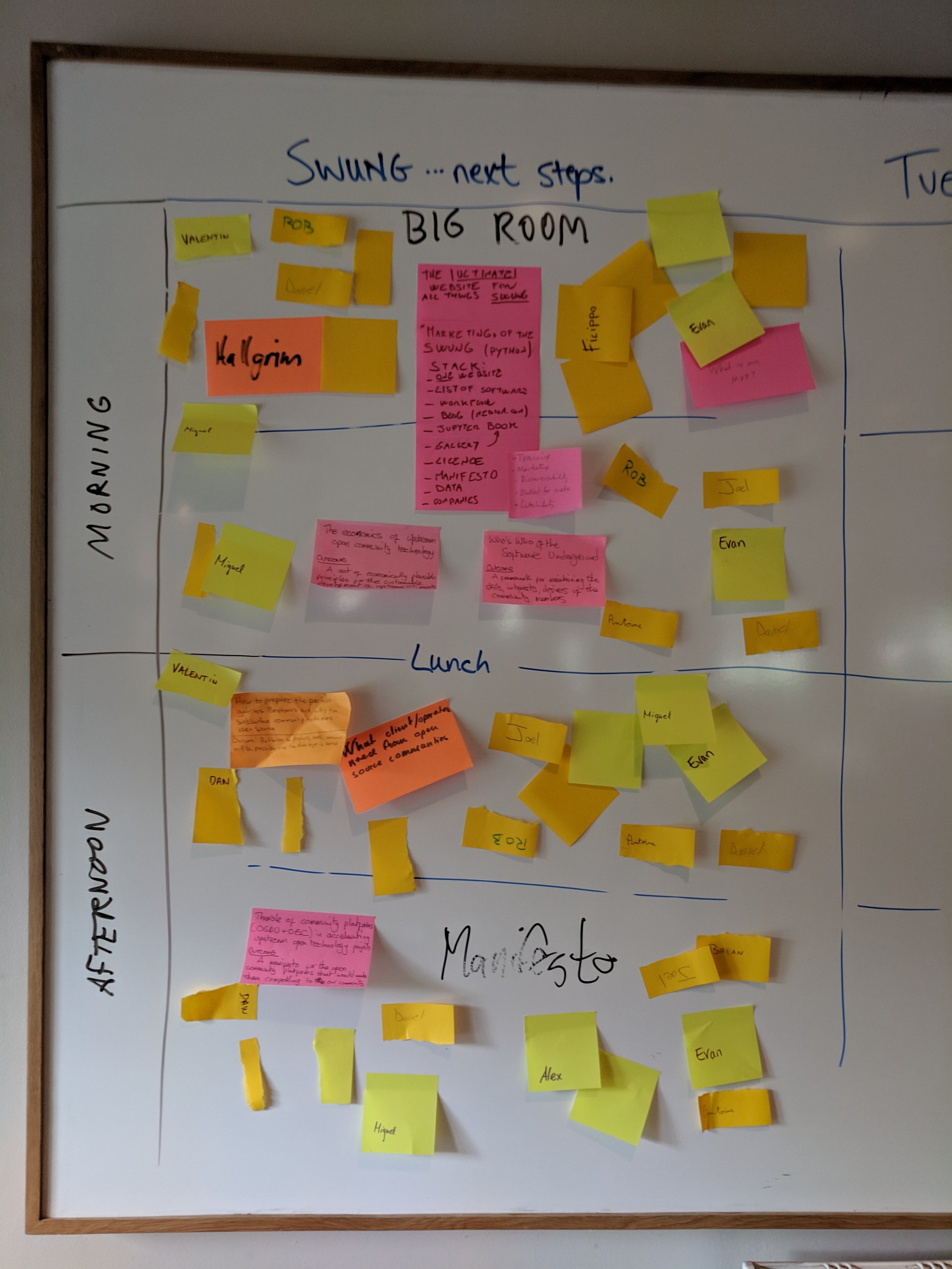

Reflective practice means asking for, and then acting on, student feedback — every day. We ask students to write it on sticky notes. Reading these back to the class the next morning is a good way to really read it. One of the many benefits of ‘never teach alone’ is always having someone to give you feedback from another teacher’s perspective too. Multi-day courses let us improve in real time, which is good for us and for the students.

Some other advice:

Keep the student:instructor ratio to no more than ten; seven or eight is better.

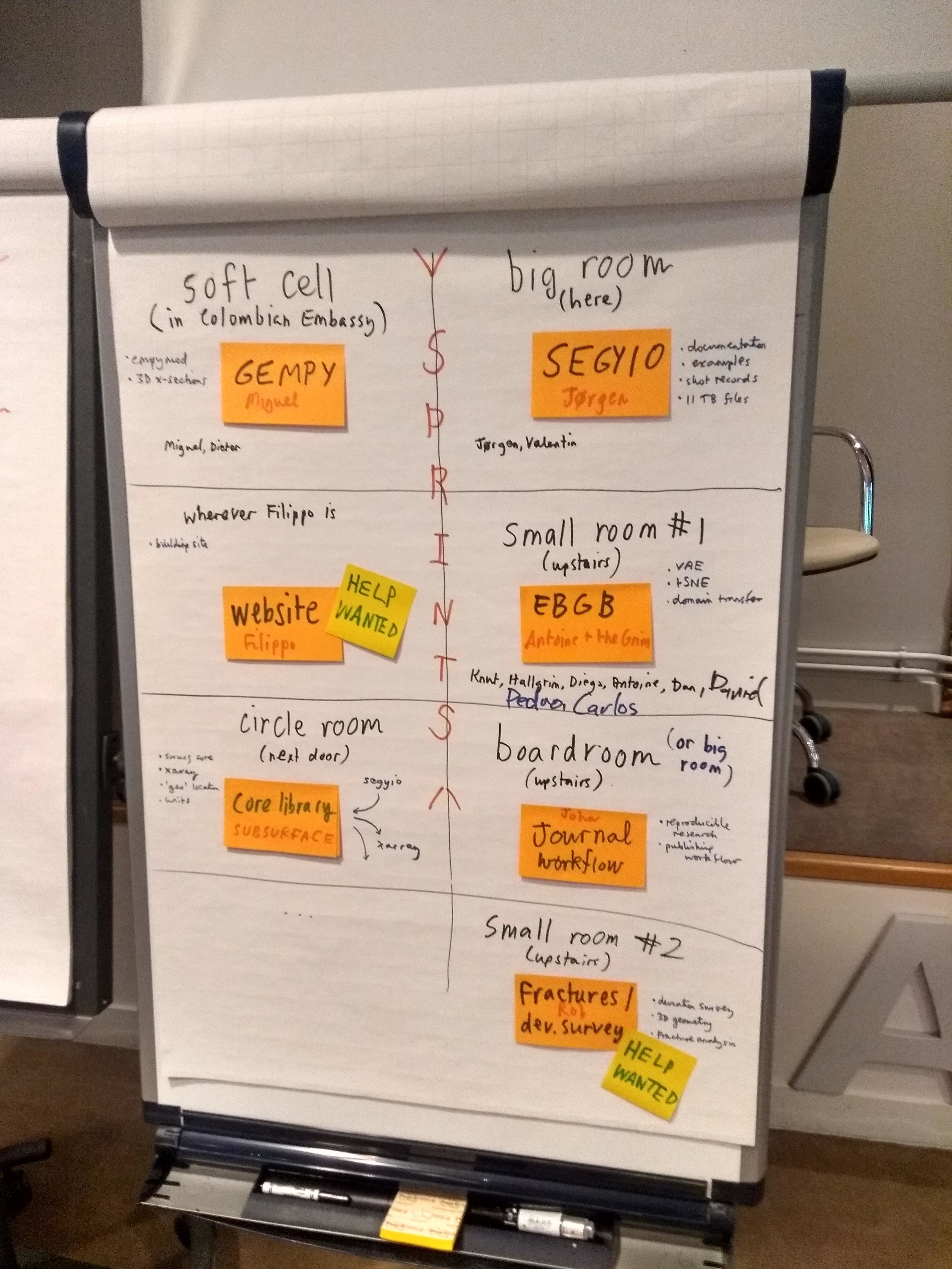

Take a packet of orange and a packet of green Post-It notes. Use them for names, as ‘help me’ flags, and for feedback.

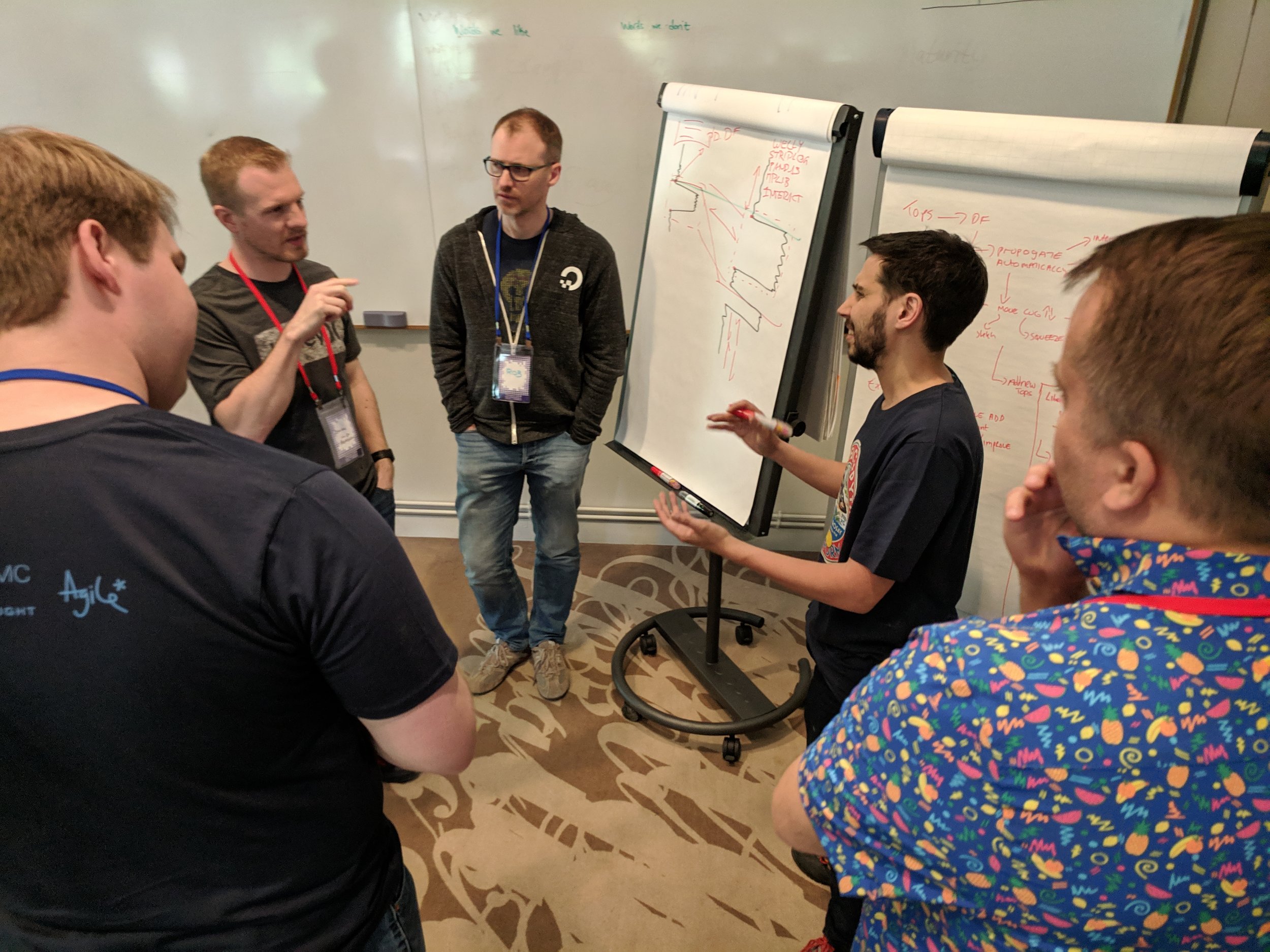

When teaching programming, the more live coding — from scratch — you can do, the better. While you code, narrate your thought process. This way, students are able to make conections between ideas, code, and mistakes.

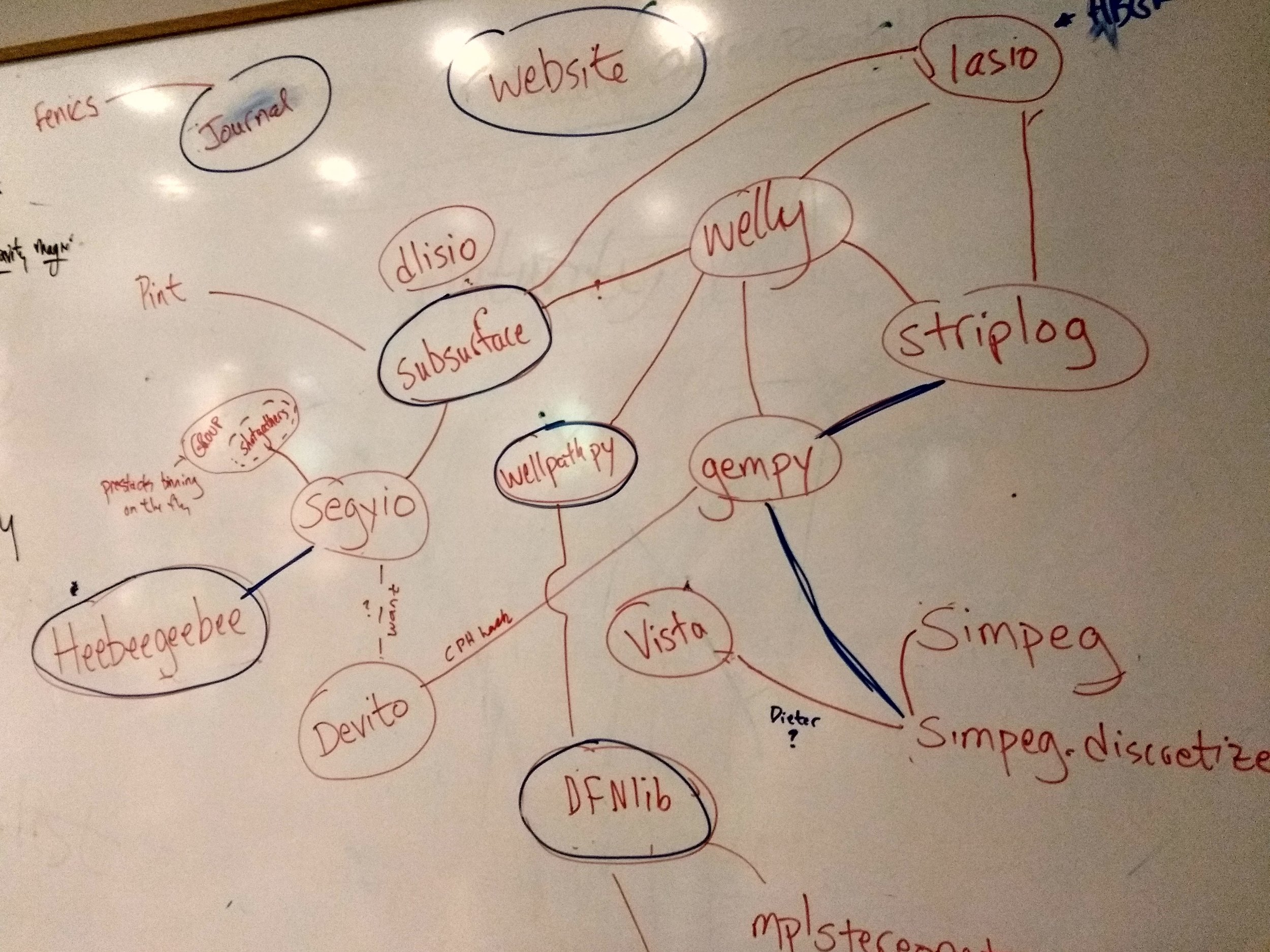

To explain concepts, draw on a whiteboard. Avoid slides whenever possible.

Our co-teacher John Leeman likes to say, “I just showed you something new, what questions do you have?” This beats “Any questions?” for opening the door to engagement.

“No-one left behind” is a nice idea, but it’s not always practical. If students can’t devote 100% to the class and then struggle because of it, you owe it to the the others to politely suggest they pick the class up again next time.

Devote some time to the practical application of the skills you’re teaching, preferably in areas of the participants’ own choosing. In our 5-day class, we devote a whole day to getting students started on their own projects.

Don’t underestimate the importance of a nice space, natural light, good food, and frequent breaks.

Recognize everyone’s achievement with a small gift at the end of the class.

Learning is hard work. Finish early every day.

Give it a try

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed