Your child is dense for her age

/Alan Cohen, veteran geophysicist and Chief Scientist at RSI, secured the role of provacateur by posting this question on the rock physics group on LinkedIn. He has shown that the simplest concepts are worthy of debate.

From a group of 1973 members, 44 comments ensued over the 23 days since he posted it. This has got to be a record for this community (trust me I've checked). It turns out the community is polarized, and heated emotions surround the topic. The responses that emerged are a fascinating narrative of niche and tacit assumptions seldomly articulated.

Any two will do

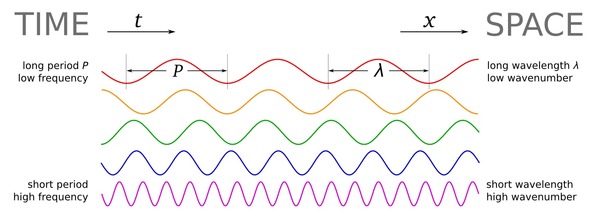

Why are two dimensions used, instead of one, three, four, or more? Well for one, it is hard to look at scatter plots in 3D. More fundamentally, a key learning from the wave equation and continuum mechanics is that, given any two elastic properties, any other two can be computed. In other words, for any seismically elastic material, there are two degrees of freedom. Two parameters to describe it.

- P- and S-wave velocities

- P-impedance and S-impedance

- Acoustic and elastic impedance

- R0 and G, the normal-incidence reflectivity and the AVO gradient

- Lamé's parameters, λ and μ

Each pair has its time and place, and as far as I can tell there are reasons that you might want to re-parameterize like this:

- one set of parameters contains discriminating evidence, not visible in other sets;

- one set of parameters is a more intuitive or more physical description of the rock—it is easier to understand;

- measurement errors and uncertainties can be elucidated better for one of the choices.

Something missing from this thread, though, is the utility of empirical templates to makes sense of the data, whichever domain is adopted.

Measurements with a backdrop

Measurements with a backdrop

In child development, body mass index (BMI) is plotted versus age to characterize a child's physical properties using the backdrop of an empirically derived template sampled from a large population. It is not so interesting to say, "13 year old Miranda has a BMI of 27", it is much more telling to learn that Miranda is above the 95th percentile for her age. But BMI, which is defined as weight divided by height squared, in not particularity intuitive. If kids were rocks, we'd submerge them Archimedes style into a bathtub, measure their volume, and determine their density. That would be the ultimate description. "Whoa, your child is dense for her age!"

We do the same things with rocks. We algebraically manipulate measured variables in various ways to show trends, correlations, or clustering. So this notion of a template is very important, albeit local in scope. Just as a BMI template for Icelandic children might not be relevant for the pygmies in Paupa New Guinea, rock physics templates are seldom transferrable outside their respective geographic regions.

For reference see the rock physics cheatsheet.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed