What is the fastest axis of an array?

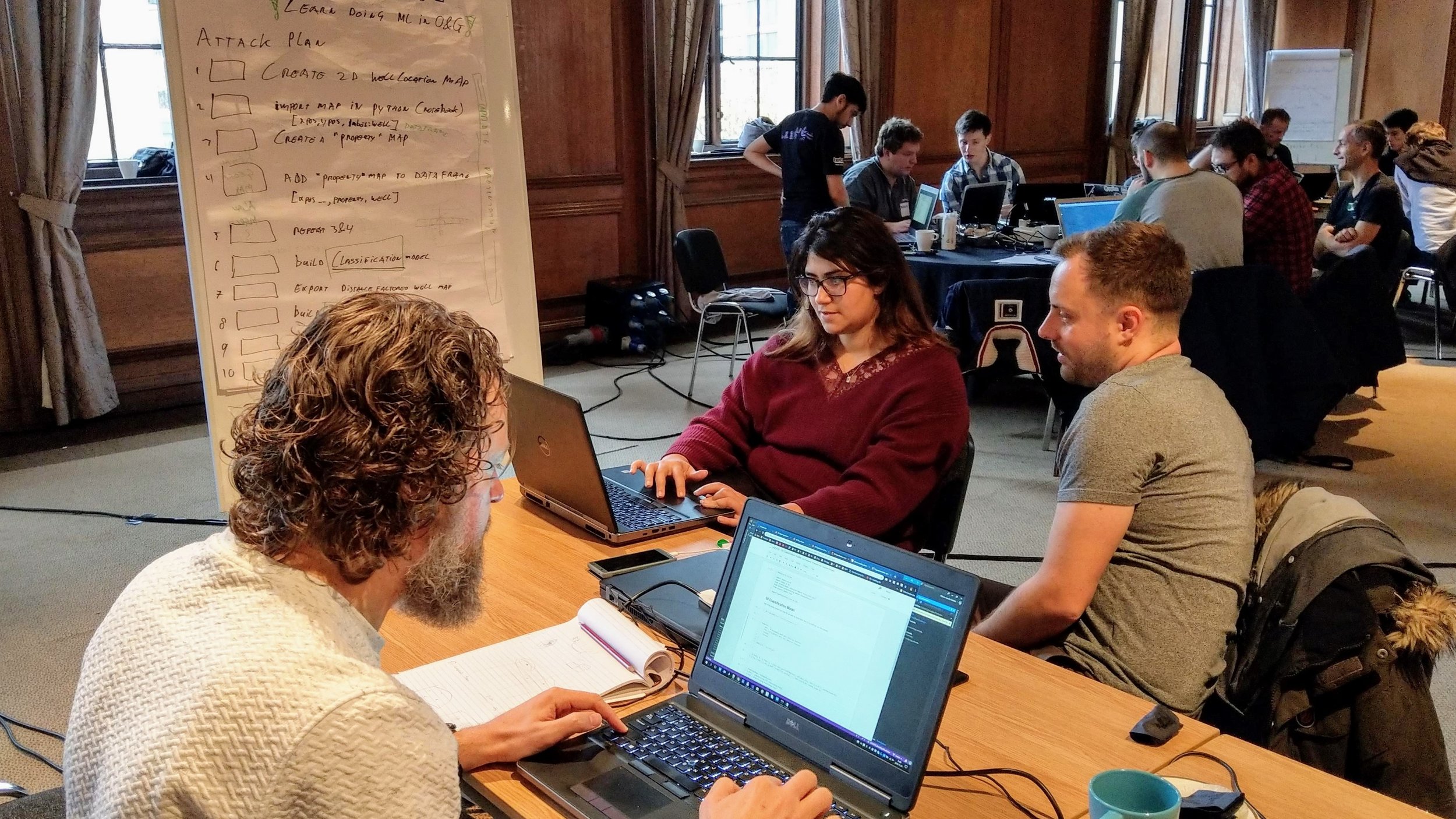

/One of the participants in our geocomputing course asked us a tricky question earlier this year. She was a C++ and Java programmer — we often teach experienced programmers who want to learn about Python and/or machine learning — and she worked mostly with seismic data. She had a question related to the performance of n-dimensional arrays: what is the fastest axis of a NumPy array?

I’ve written before about how computational geoscience is not ‘software engineering’ and not ‘computer science’, but something else. And there’s a well established principle in programming, first expressed by Michael Jackson:

“We follow two rules in the matter of optimization:

Rule 1: Don’t do it.

Rule 2 (for experts only). Don’t do it yet — that is, not until you have a perfectly clear and unoptimized solution.”

Most of the time the computer is much faster than we need it to be, so we don’t spend too much time thinking about making our programs faster. We’re mostly concerned with making them work, then making them correct. But sometimes we have to think about speed. And sometimes that means writing smarter code. (Other times it means buying another GPU.) If your computer spends its days looping over seismic volumes extracting slices for processing, you should probably know whether you want to put time in the first dimension or the last dimension of your array.

The 2D case

Let’s think about a two-dimensional case first — imagine a small 2D array, also known as a matrix in some contexts. I’ve coloured in the elements of the matrix to make the next bit easier to understand.

When we store a matrix in a computer (or an image, or any array), we have a decision to make. In simple terms, the computer’s memory is like a long row of boxes, each with a unique address — shown here as a 3-digit hexadecimal number:

We can only store one number in each box, so we’re going to have to flatten the 2D array. The question is, do we put the rows in together, effectively splitting up the columns, or do we put the columns in together? These two options are commonly known as ‘row major’, or C-style, and ‘column major’, or Fortran-style:

Let’s see what this looks like in terms of the indices of the elements. We can plot the index number on each axis vs. the position of the element in memory. Notice that the C-ordered elements are contiguous in axis 0:

If you spend a lot of time loading seismic data, you probably recognize this issue — it’s analgous to how traces are stored in a SEG-Y file. Of couse, with seismic data, two dimensions aren’t always enough…

Higher dimensions

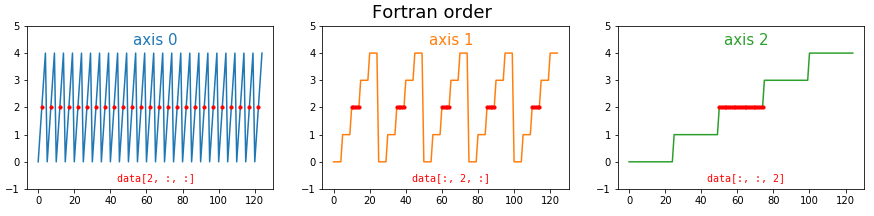

The problem multiplies at higher dimensions. If we have a cube of data, then C-style ordering results in the first dimension having large contiguous chunks, and the last dimension being broken up. The middle dimension is somewhere in between. As before, we can illustrating this by plotting the indices of the data. This time I’m highlighting the positions of the elements with index 2 (i.e. the third element) in each dimension:

So if this was a seismic volume, we might organize inlines in the first dimension, and travel-time in the last dimension. That way, we can access inlines very quickly, but timeslices will take longer.

In Fortran order, which we can optionally specify in NumPy, the situation is reversed. Now the fast axis is the last axis:

Lots of programming languages and libraries use row-major memory layout, including C, C++, Torch and NumPy. Most others use column-major ordering, including MATLAB, R, Julia, and Fortran. (Some other languages, such as Java and .NET, use a variant of row-major order called Iliffe vectors). NumPy calls row-major order ‘C’ (for C, not for column), and column-major ‘F’ for Fortran (thankfully they didn’t use R, for R not for row).

I expect it’s related to their heritage, but the Fortran-style languages also start counting at 1, whereas the C-style languages, including Python, start at 0.

What difference does it make?

The main practical difference is in the time it takes to access elements in different orientations. It’s faster for the computer to take a contiguous chunk of neighbours from the memory ‘boxes’ than it is to have to ‘stride’ across the memory taking elements from here and there.

How much faster? To find out, I made datasets full of random numbers, then selected slices and added 1 to them. This was the simplest operation I could think of that actually forces NumPy to do something with the data. Here are some statistics — the absolute times are pretty irrelevant as the data volumes I used are all different sizes, and the speeds will vary on different machines and architectures:

2D data: 3.6× faster. Axis 0: 24.4 µs, axis 1: 88.1 µs (times relative to first axis: 1, 3.6).

3D data: 43× faster. 229 µs, 714 µs, 9750 µs (relatively 1, 3.1, 43).

4D data: 24× faster. 1.27 ms, 1.36 ms, 4.77 ms, 30 ms (relatively 1, 1.07, 3.75, 23.6).

5D data: 20× faster. 3.02 ms, 3.07 ms, 5.42 ms, 11.1 ms, 61.3 ms (relatively 1, 1.02, 1.79, 3.67, 20.3).

6D data: 5.5× faster. 24.4 ms, 23.9 ms, 24.1 ms, 37.8 ms, 55.3 ms, 136 ms (relatively 1, 0.98, 0.99, 1.55, 2.27, 5.57).

These figures are more or less simply reversed for Fortran-ordered arrays (see the notebook for datails).

Clearly, the biggest difference is with 3D data, so if you are manipulating seismic data a lot and need to access the data in that last dimension, usually travel-time, you might want to think about ways to reduce this overhead.

What difference does it really make?

The good news is that, for most of us most of the time, we don’t have to worry about any of this. For one thing, NumPy’s internal workings (in particular, its universal functions, or ufuncs) know which directions are fastest and take advantage of this when possible. For another thing, we generally try to avoid looping over arrays at all, leaving the iterative components of our algorithms to the ufuncs — so the slicing speed isn’t a factor. Even when it is a factor, or if we can’t avoid looping, it’s often not the bottleneck in the code. Usually the guts of our algorithm are what are slowing the computer down, not the access to memory. The net result of all this is that we don’t often have to think about the memory layout of our arrays.

So when does it matter? The following situations merit a bit of thought:

When you’re doing a very large number of accesses to memory or disk. Saving a few microseconds might add up to a lot if you’re doing it a billion times.

When the objects you’re accessing are very large. Reading and writing elements of a 200GB array in memory brings new challenges compared to handling a few gigabytes.

Reading and writing data files — really just another kind of memory — brings all the same issues. Reading a chunk of contiguous data is much faster than reading bytes from here and there. Landmark’s BRI seismic data format, Schlumberger’s ZGY files, and HDF5 files, all implement strategies to help make reading arbitrary data faster.

Converting code from other languages, especially MATLAB, although do realize that other languages may have their own indexing rules, as well as differing in how they store n-dimensional arrays.

If you determine that you do need to think about this stuff, then you’re going to need to read this essay about NumPy’s internal representations, and I recommend checking out this blog post by Eli Bendersky too.

There you have it. Very occasionally we scientists also need to think a bit about how computers work… but most of the time someone has done that thinking for us.

Some of the figures and all of the timings for this post came from this notebook — please have a look. If you have anything to add, or (better yet) correct, please get in touch. I’d love to hear from you.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed