Hacking in Houston

/Houston 2013

Houston 2014

Denver 2014

Calgary 2015

New Orleans 2015

Vienna 2016

Paris 2017

Houston 2017... The eighth geoscience hackathon landed last weekend!

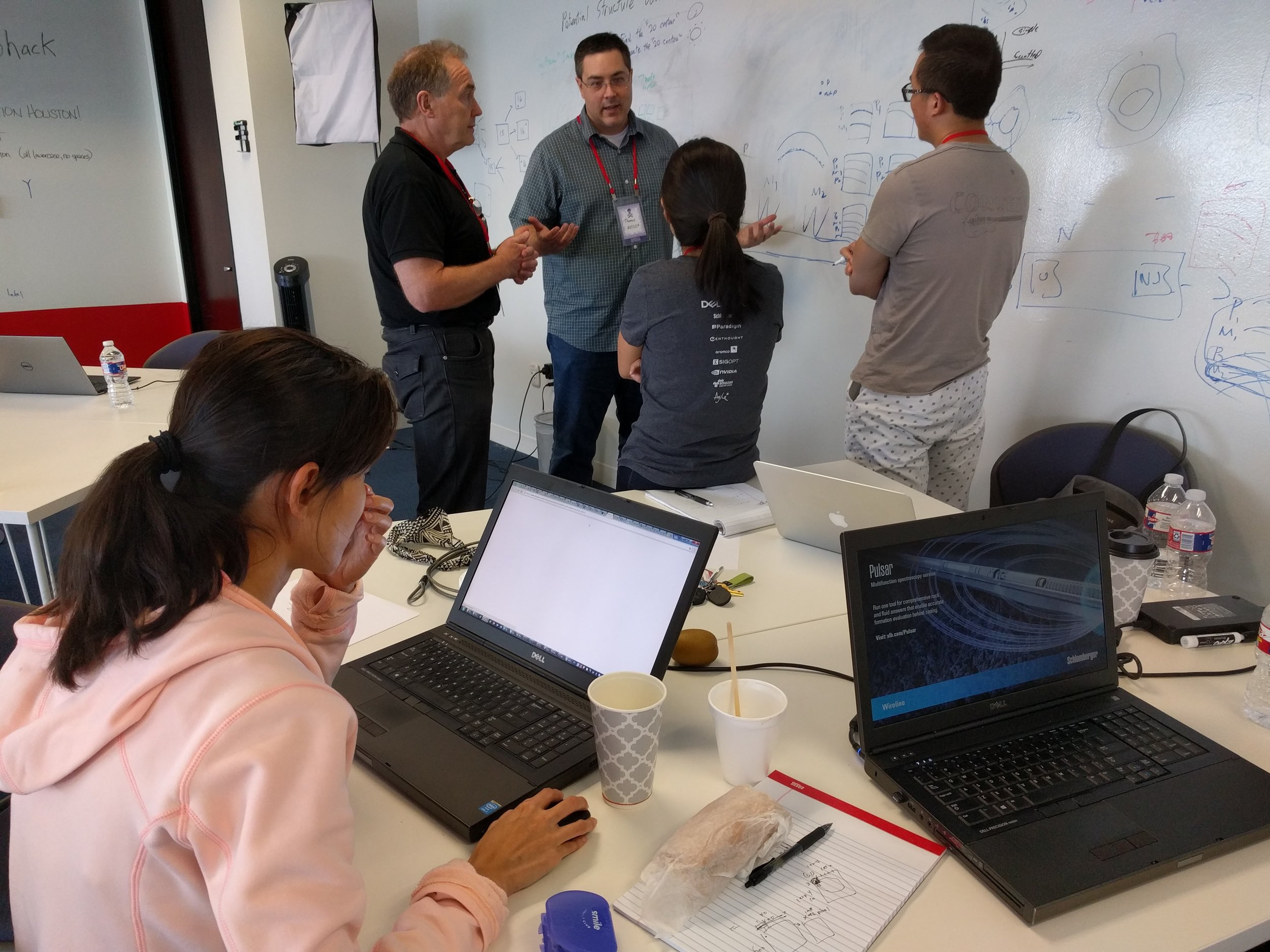

We spent last weekend in hot, humid Houston, hacking away with a crowd of geoscience and technology enthusiasts. Thirty-eight hackers joined us on the top-floor coworking space, Station Houston, for fun and games and code. And tacos.

Here's a rundown of the teams and what they worked on.

Seismic Imagers

Jingbo Liu (CGG), Zohreh Souri (University of Houston).

Tech — DCGAN in Tensorflow, Amazon AWS EC2 compute.

The team looked for patterns that make seismic data different from other images, using a deep convolutional generative adversarial network (DCGAN). Using a seismic volume and a set of 2D lines, they made 121,000 sub-images (tiles) for their training set.

The Young And The RasLAS

William Sanger (Schlumberger), Chance Sanger (Museum of Fine Arts, Houston), Diego Castañeda (Agile), Suman Gautam (Schlumberger), Lanre Aboaba (University of Arkansas).

State of the art text detection by Google Cloud Vision API

Tech — Google Cloud Vision API, Python flask web app, Scatteract (sort of). Repo on GitHub.

Digitizing well logs is a common industry task, and current methods require a lot of manual intervention. The team's automated pipeline: convert PDF files to images, perform OCR with Google Cloud Vision API to extract headers and log track labels, pick curves using a CNN in TensorFlow. The team implemented the workflow in a Python flask front-end. Check out their slides.

Hutton Rocks

Kamal Hami-Eddine (Paradigm), Didi Ooi (University of Bristol), James Lowell (GeoTeric), Vikram Sen (Anadarko), Dawn Jobe (Aramco).

Tech — Amazon Echo Dot, Amazon AWS (RDS, Lambda).

The team built Hutton, a cloud-based cognitive assistant for gaining more efficient, better insights from geologic data. Project includes integrated cloud-hosted database, interactive web application for uploading new data, and a cognitive assistant for voice queries. Hutton builds upon existing Amazon Alexa skills. Check out their GitHub repo, and slides.

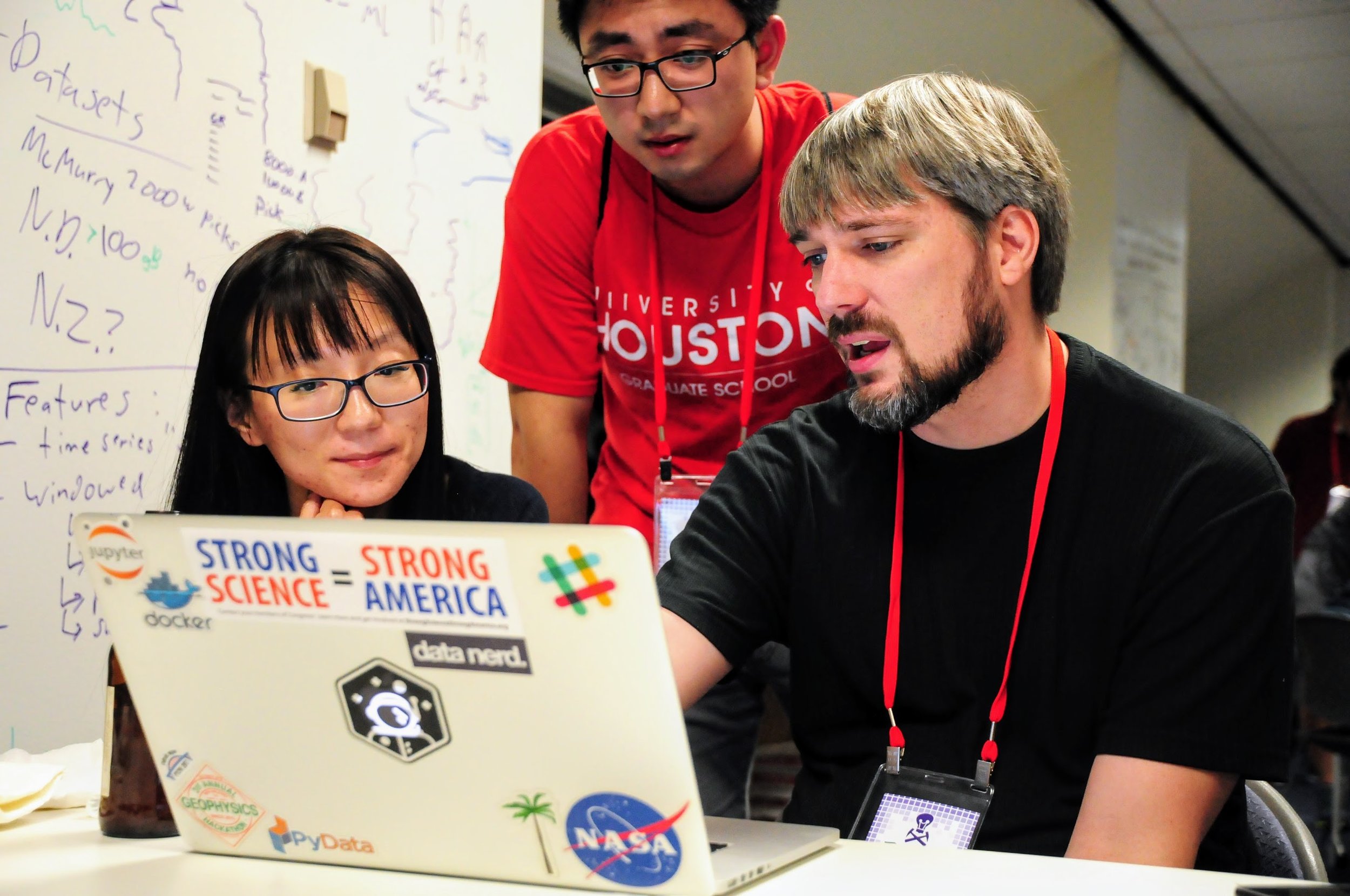

Big data > Big Lore

Licheng Zhang (CGG), Zhenzhen Zhong (CGG), Justin Gosses (Valador/NASA), Jonathan Parker (Marathon)

The team used machine learning to predict formation tops on wireline logs, which would allow for rapid generation of structure maps for exploration play evaluation, save man hours and assist in difficuly formation-top correlations. The team used the AER Athabasca open dataset of 2193 wells (yay, open data!).

Tech — Jupyter Notebooks, SciPy, scikit-learn. Repo on GitHub.

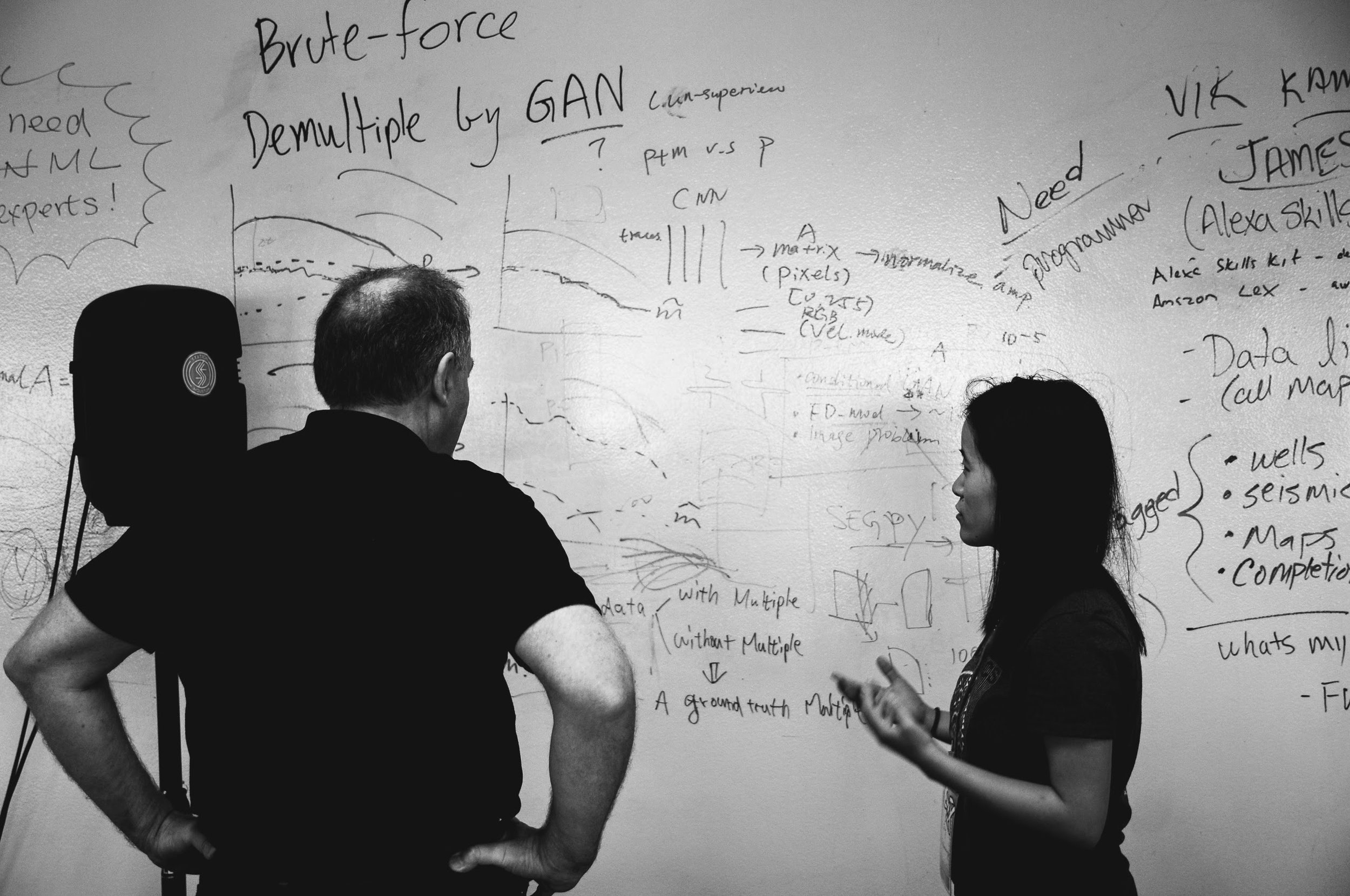

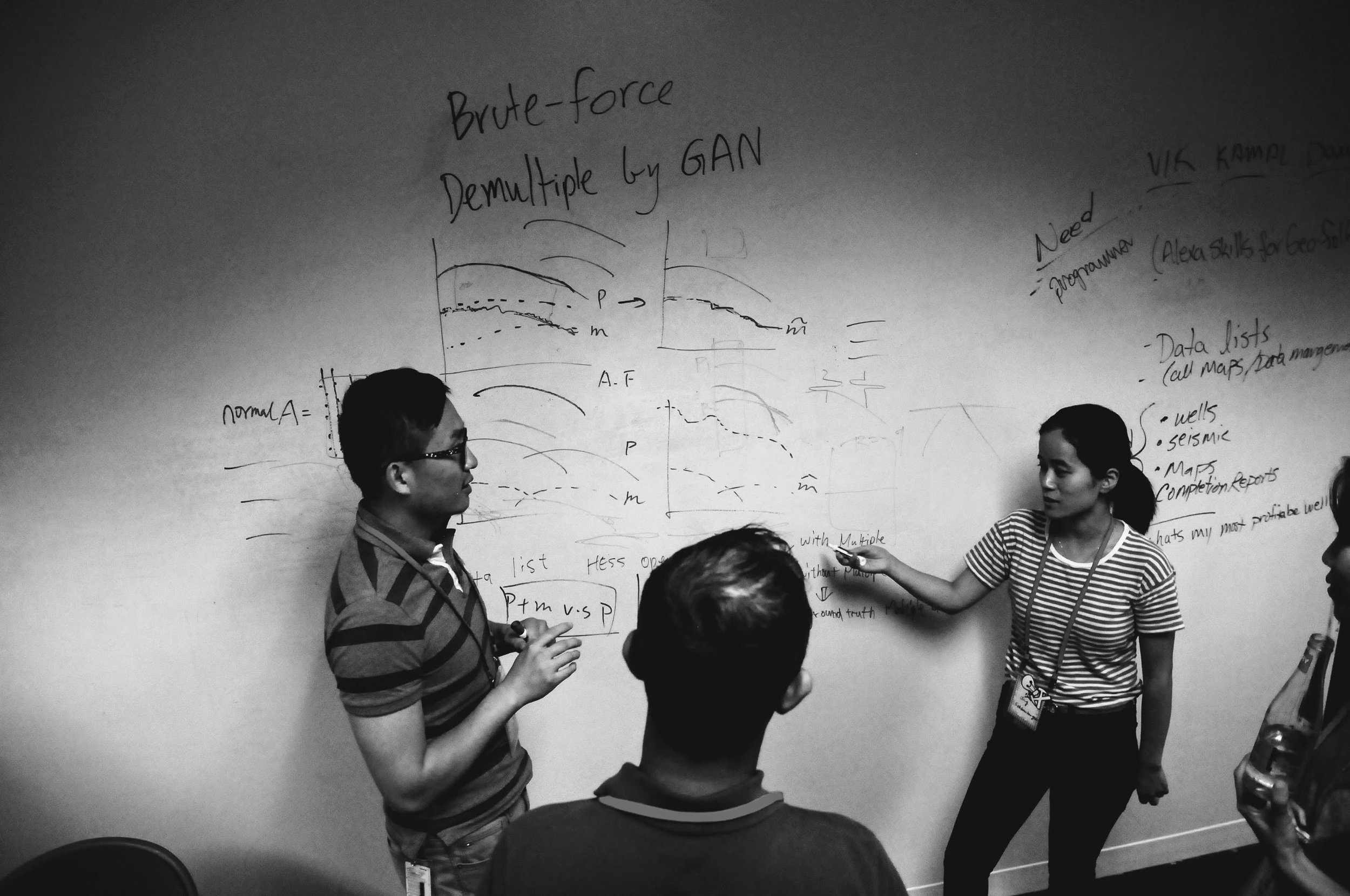

Free near surface

Tien-Huei Wang, Jing Wu, Clement Zhang (Schlumberger).

Multiples are a kind of undesired seismic signal and take expensive modeling to remove. The project used machine learning to identify multiples in seismic images. They attempted to use GAN frameworks, but found it difficult to formulate their problem, turning instead to the simpler problem of binary classification. Check out their slides.

Tech — CNN... I don't know the framework.

The Cowboyz

Mingliang Liu, Mohit Ayani, Xiaozheng Lang, Wei Wang (University of Wyoming), Vidal Gonzalez (Universidad Simón Bolívar, Venezuela).

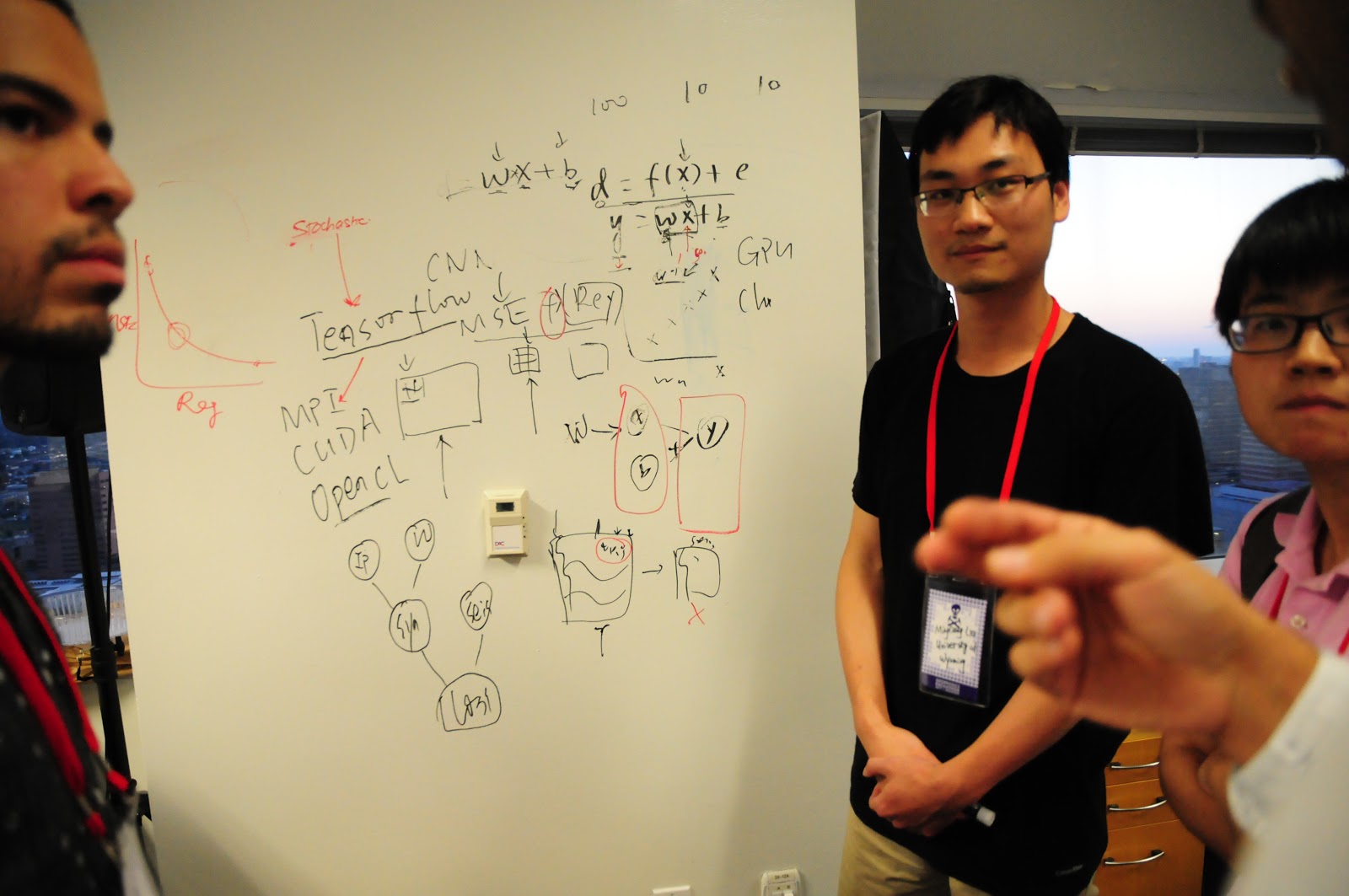

A tight group of researchers joined us from the University of Wyoming at Laramie, and snagged one of the most enthusiastic hackers at the event, a student from Venezuela called Vidal. The team attempted acceleration of geostatistical seismic inversion using TensorFlow, a central theme in Mingliang's research.

Tech — TensorFlow.

Augur.ai

Altay Sensal (Geokinetics), Yan Zaretskiy (Aramco), Ben Lasscock (Geokinetics), Colin Sturm (Apache), Brendon Hall (Enthought).

Electrical submersible pumps (ESPs) are critical components for oil production. When they fail, they can cause significant down time. Augur.ai provides tools to analyze pump sensor data to predict when pumps when pump are behaving irregularly. Check out their presentation!

Tech — Amazon AWS EC2 and EFS, Plotly Dash, SigOpt, scikit-learn. Repo on GitHub.

The Disaster Masters

Joe Kington (Planet), Brendan Sullivan (Chevron), Matthew Bauer (CSM), Michael Harty (Oxy), Johnathan Fry (Chevron)

Hydrologic models predict floodplain flooding, but not local street flooding. Can we predict street flooding from LiDAR elevation data, conditioned with citizen-reported street and house flooding from U-Flood? Maybe! Check out their slides.

Tech — Python geospatial and machine learning stacks: rasterio, shapely, scipy.ndimage, scikit-learn. Repo on GitHub.

The structure does WHAT?!

Chris Ennen (White Oak), Nanne Hemstra (dGB Earth Sciences), Nate Suurmeyer (Shell), Jacob Foshee (Durwella).

Inspired by the concept of an iPhone 'face ageing' app, Nate recruited a team to poke at applying the concept to maps of the subsurface. Think of a simple map of a structural field early in its life, compared to how it looks after years of interpretation and drilling. Maybe we can preview the 'aged' appearance to help plan where best to drill next to reduce uncertainty!

Tech — OpendTect, Azure ML Studio, C#, self-boosting forest cluster. Repo on GitHub.

Thank you!

Massive thanks to our sponsors — including Pioneer Natural Resources — for their part in bringing the event to life!

More thank-yous

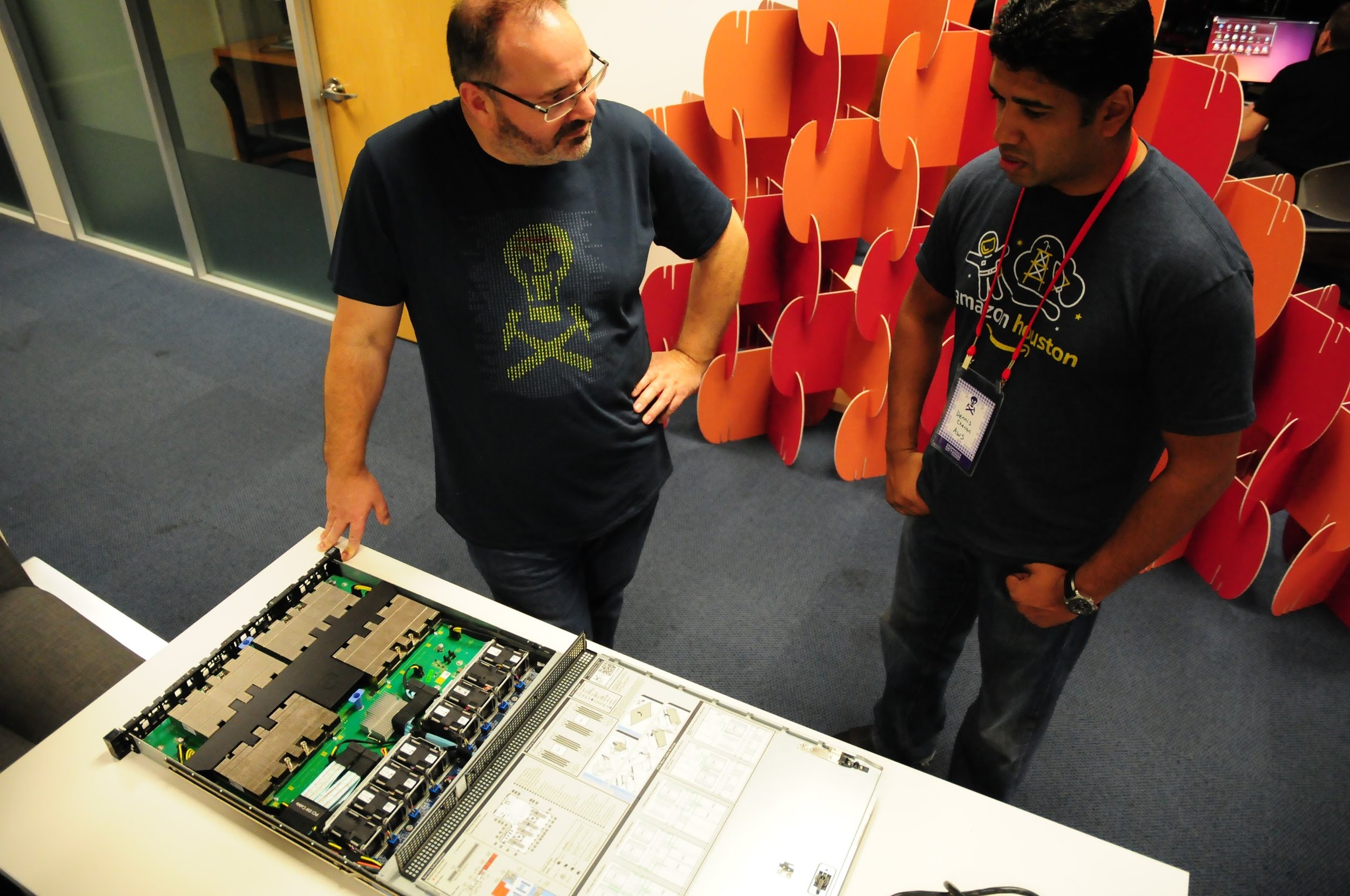

Apart from the participants themselves, Evan and I benefitted from a team of technical support, mentors, and judges — huge thanks to all these folks:

- The indefatigable David Holmes from Dell EMC. The man is a legend.

- Andrea Cortis from Pioneer Natural Resources.

- Francois Courteille and Issam Said of NVIDIA.

- Carlos Castro, Sunny Sunkara, Dennis Cherian, Mike Lapidakis, Jit Biswas, and Rohan Mathews of Amazon AWS.

- Maneesh Bhide and Steven Tartakovsky of SigOpt.

- Dave Nichols and Aria Abubakar of Schlumberger.

- Eric Jones from Enthought.

- Emmanuel Gringarten from Paradigm.

- Frances Buhay and Brendon Hall for help with catering and logistics.

- The team at Station for accommodating us.

- Frank's Pizza, Tacos-a-Go-Go, Cali Sandwich (banh mi), Abby's Cafe (bagels), and Freebird (burritos) for feeding us.

Finally, megathanks to Gram Ganssle, my Undersampled Radio co-host. Stalwart hack supporter and uber-fixer, Gram came over all the way from New Orleans to help teams make sense of deep learning architectures and generally smooth things over. We recorded an episode of UR at the hackathon, talking to Dawn Jobe, Joe Kington, and Colin Sturm about their respective projects. Check it out!

[Update, 29 Sep & 3 Nov] Some statistics from the event:

- 39 participants, including 7 women (way too few, but better than 4 out of 63 in Paris)

- 9 students (and 0 professors!).

- 12 people from petroleum companies.

- 18 people from service and technology companies, including 5 from Schlumberger!

- 13 no-shows, not including folk who cancelled ahead of time; a bit frustrating because we had a long wait list.

- Furthest travelled: James Lowell from Newcastle, UK — 7560 km!

- 98 tacos, 67 burritos, 96 slices of pizza, 55 kolaches, and an untold number of banh mi.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed