Volve: not open after all

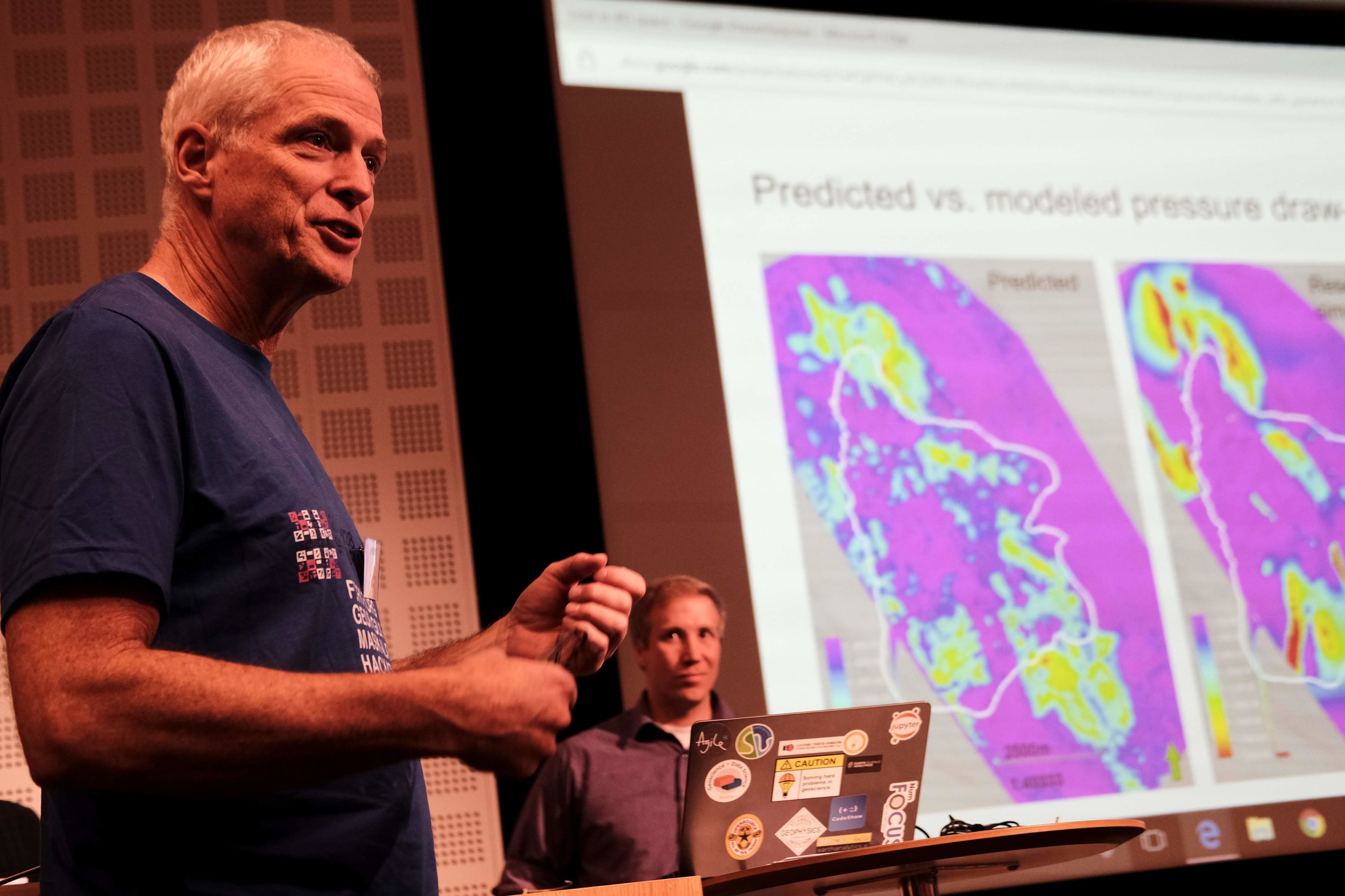

/Back in June, Equinor made the bold and exciting decision to release all its data from the decommissioned Volve oil field in the North Sea. Although the intent of the release seemed clear, the dataset did not carry a license of any kind. Since you cannot use unlicensed content without permission, this was a problem. I wrote about this at the time.

To its credit, Equinor listened to the concerns from me and others, and considered its options. Sensibly, it chose an off-the-shelf license. It announced its decision a few days ago, and the dataset now carries a Creative Commons Attribution-NonCommercial-ShareAlike license.

Unfortunately, this license is not ‘open’ by any reasonable definition. The non-commercial stipulation means that a lot of people, perhaps most people, will not be able to legally use the data (which is why non-commercial licenses are not open licenses). And the ShareAlike part means that we’re in for some interesting discussion about what derived products are, because any work based on Volve will have to carry the CC BY-NC-SA license too.

Non-commercial licenses are not open

Here are some of the problems with the non-commercial clause:

NC licenses are not 'open'. They do not meet the Open Definition, because open data must be available for anyone to use, for any purpose. For example, here’s a quote from Hagedorn et al (2011):

NC licenses come at a high societal cost: they provide a broad protection for the copyright owner, but strongly limit the potential for re-use, collaboration and sharing in ways unexpected by many users

NC licenses are incompatible with CC-BY-SA. This means that the data cannot be used on Wikipedia, SEG Wiki, or AAPG Wiki, or in any openly licensed work carrying that license.

NC-licensed data cannot be used commercially. This is obvious, but far-reaching. It means, for example, that nobody can use the data in a course or event for which they charge a fee. It means nobody can use the data as a demo or training data in commercial software. It means nobody can use the data in a book that they sell.

The boundaries of the license are unclear. It's arguable whether any business can use the data for any purpose at all, because many of the boundaries of the scope have not been tested legally. What about a course run by AAPG or SEG? What about a private university? What about a government, if it stands to realize monetary gain from, say, a land sale? All of these uses would be illiegal, because it’s the use that matters, not the commercial status of the user.

Now, it seems likely, given the language around the release, that Equinor will not sue people for most of these use cases. They may even say this. Goodness knows, we have enough nudge-nudge-wink-wink agreements like that already in the world of subsurface data. But these arrangements just shift the onus onto the end use and, as we’ve seen with GSI, things can change and one day you wake up with lawsuits.

ShareAlike means you must share too

Creative Commons licenses are, as the name suggests, intended for works of creativity. Indeed, the whole concept of copyright, depends on creativity: copyright protects works of creative expression. If there’s no creativity, there’s no basis for copyright. So for example, a gamma-ray log is unlikely to be copyrightable, but seismic data is (follow the GSI link above to find out why). Non-copyrightable works are not covered by Creative Commons licenses.

All of which is just to help explain some of the language in the CC BY-NC-SA license agreement, which you should read. But the key part is in paragraph 4(b):

You may distribute, publicly display, publicly perform, or publicly digitally perform a Derivative Work only under the terms of this License

What’s a ‘derivative work’? It’s anything ‘based upon’ the licensed material, which is pretty vague and therefore all-encompassing. In short, if you use or show Volve data in your work, no matter how non-commercial it is, then you must attach a CC BY-NC-SA license to your work. This is why SA licenses are sometimes called ‘viral’.

By the way, the much-loved F3 and Penobscot datasets also carry the ShareAlike clause, so any work (e.g. a scientific paper) that uses them is open-access and carries the CC BY-SA license, whether the author of that work likes it or not. I’m pretty sure no-one in academic publishing knows this.

By the way again, everything in Wikipedia is CC BY-SA too. Maybe go and check your papers and presentations now :)

What should Equinor do?

My impression is that Equinor is trying to satisfy some business partner or legal edge case, but they are forgetting that they have orders of magnitude more capacity to deal with edge cases than the potential users of the dataset do. The principle at work here should be “Don’t solve problems you don’t have”.

Encumbering this amazing dataset with such tight restrictions effectively kills it. It more or less guarantees it cannot have the impact I assume they were looking for. I hope they reconsider their options. The best choice for any open data is CC-BY.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed