PRESS START

/The dust has settled from the Subsurface Hackathon 2016 in Vienna, which coincided with EAGE's 78th Conference and Exhibition (some highlights). This post builds on last week's quick summary with more detailed descriptions of the teams and what they worked on. If you want to contact any of the teams, you should be able to track them down via the links to Twitter and/or GitHub.

A word before I launch into the projects. None of the participants had built a game before. Many were relatively new to programming — completely new in one or two cases. Most of the teams were made up of people who had never worked together on a project before; indeed, several team mates had never met before. So get ready to be impressed, maybe even amazed, at what members of our professional community can do in 2 days with only mild provocation and a few snacks.

Traptris

An 8-bit-style video game, complete with music, combining Tetris with basin modeling.

Team: Chris Hamer, Emma Blott, Natt Turner (all MSc students at the University of Leeds), Jesper Dramsch (PhD student, Technical University of Denmark, Copenhagen). GitHub repo.

Tech: Python, with PyGame.

Details: The game is just like Tetris, except that the blocks have lithologies: source, reservoir, and seal. As you complete a row, it disappears, as usual. But in this game, the row reappears on a geological cross-section beside the main game. By completing further rows with just-right combinations of lithologies, you build an earth model. When it's deep enough, and if you've placed sources rocks in the model, the kitchen starts to produce hydrocarbons. These migrate if they can, and are eventually trapped — if you've managed to build a trap, that is. The team impressed the judges with their solid gamplay and boisterous team spirit. Just installing PyGame and building some working code was an impressive feat for the least experienced team of the hackathon.

Prize: We rewarded this rambunctious team for their creative idea, which it's hard to imagine any other set of human beings coming up with. They won Samsung Gear VR headsets, so I'm looking forward to the AR version of the game.

Flappy Trace

A ridiculously addictive seismic interpretation game. "So seismic, much geology".

Team: Håvard Bjerke (Roxar, Oslo), Dario Bendeck (MSc student, Leeds), and Lukas Mosser (PhD student, Imperial College London).

Tech: Python, with PyGame. GitHub repo.

Details: You start with a trace on the left of the screen. More traces arrive, slowly at first, from the right. The controls move the approaching trace up and down, and the pick point is set as it moves across the current trace and off the screen. Gradually, an interpretation is built up. It's like trying to fly along a seismic horizon, one trace at a time. The catch is that the better you get, the faster it goes. All the while, encouragements and admonishments flash up, with images of the doge meme. Just watching someone else play is weirdly mesmerizing.

Prize: The judges wanted to recognize this team for creating such a dynamic, addictive game with real personality. They won DIY Gamer kits and an awesome book on programming Minecraft with Python.

Guess What!

Human seismic inversion. The player must guess the geology that produces a given trace.

Team: Henrique Bueno dos Santos, Carlos Andre (both UNICAMP, Sao Paolo), and Steve Purves (Euclidity, Spain)

Tech: Python web application, on Flask. It even used Agile's nascent geo-plotting library, g3.js, which I am pretty excited about. GitHub repo. You can even play the game online!

Details: This project was on a list of ideas we crowdsourced from the Software Underground Slack, and I really hoped someone would give it a try. The team consisted of a postdoc, a PhD student, and a professional developer, so it's no surprise that they managed a nice implementation. The player is presented with a synthetic seismic trace and must place reflection coefficients that will, she hopes, forward model to match the trace. She may see how she's progressing only a limited number of times before submitting her final answer, which receives a score. There are so many ways to control the game play here, I think there's a lot of scope for this one.

Prize: This team impressed everyone with the far-reaching implications of the game — and the rich possibilities for the future. They were rewarded with SparkFun Digital Sandboxes and a copy of The Thrilling Adventures of Lovelace and Babbage.

DiamondChaser

aka DiamonChaser (sic). A time- and budget-constrained drilling simulator aimed at younger players.

Team: Paul Gabriel, Björn Wieczoreck, Daniel Buse, Georg Semmler, and Jan Gietzel (all at GiGa infosystems, Freiberg)

Tech: TypeScript, which compiles to JS. BitBucket repo. You can play the game online too!

Details: This tight-knit group of colleagues — all professional developers, but using unfamiliar technology — produced an incredibly polished app for the demo. The player is presented with a blank cross section, and some money. After choosing what kind of drill bit to start with, the drilling begins and the subsurface is gradually revealed. The game is then a race against the clock and the ever-diminishing funds, as diamonds and other bonuses are picked up along the way. The team used geological models from various German geological surveys for the subsurface, adding a bit of realism.

Prize: Everyone was impressed with the careful design and polish of the app this team created, and the quiet industry they brought to the event. They each won a CellAssist OBD2 device and a copy of Charles Petzold's Code.

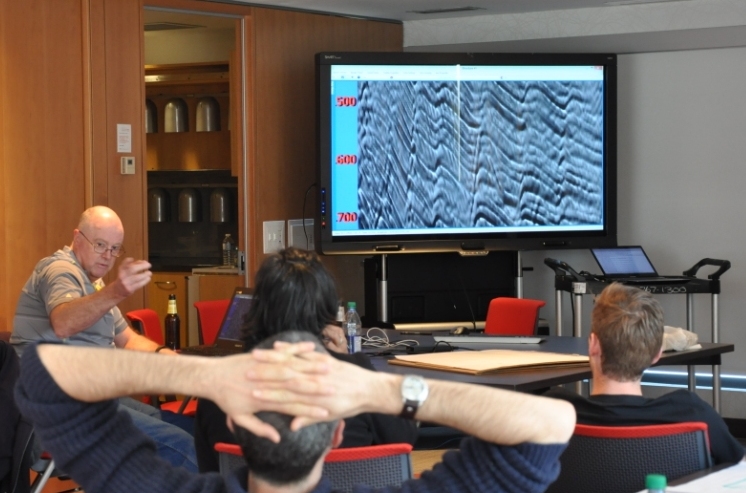

Some of the participants waiting for the judges to finish their deliberations. Standing, from left: Håvard Bjerke, Henrique Bueno dos Santos, Steve Purves. Seated: Jesper Dramsch, Lukas Mosser, Natt Turner, Emma Blott, Dario Bendeck, Carlos André, Björn Wieczoreck, Paul Gabriel.

Credits and acknowledgments

Thank you to all the hackers for stepping into the unknown and coming along to the event. I think it was everyone's first hackathon. It was an honour to meet everyone. Special thanks to Jesper Dramsch for all the help on the organizational side, and to Dragan Brankovic for taking care of the photography.

The Impact HUB Vienna was a terrific venue, providing us with multiple event spaces and plenty of room to spread out. HUB hosts Steliana and Laschandre were a great help. Der Mann produced the breakfasts. Il Mare pizzeria provided lunch on Saturday, and Maschu Maschu on Sunday.

Thank you to Kristofer Tingdahl, CEO of dGB Earth Sciences and a highly technical, as well as thoughtful, geoscientist. He graciously agreed to act as a judge for the demos, and I think he was most impressed with the quality of the teams' projects.

Last but far from least, a huge Thank You to the sponsor of the event, EMC, the cloud computing firm that was acquired by Dell late last year. David Holmes, the company's CTO (Energy) was also a judge, making an amazing opportunity for the hackers to show off their skills, and sense of humour, to a progressive company with big plans for our industry.

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed