Weekend worship in Salt Lake City

/The Salt Lake City hackathon — only the second we've done with a strong geology theme — is a thing of history, but you can still access the event page to check out who showed up and who did what. (This events page is a new thing we launched in time for this hackathon; it will serve as a public document of what happens at our events, in addition to being a platform for people to register, sponsor, and connect around our events.)

In true seat-of-the-pants hackathon style we managed to set up an array of webcams and microphones to record the finale. The demos are the icing on the cake. Teams were selected at random and were given 4 minutes to wow the crowd. Here is the video, followed by a summary of what each team got up to...

Unconformist.ai

Didi Ooi (University of Bristol), Karin Maria Eres Guardia (Shell), Alana Finlayson (UK OGA), Zoe Zhang (Chevron). The team used machine learning the automate the mapping of unconformities in subsurface data. One of the trickiest parts is building up a catalog of data-model pairs for GANs to train on. Instead of relying on thousand or hundreds of thousands of human-made seismic interpretations, the team generated training images by programmatically labelling pixels on synthetic data as being either above (white) or below (black) the unconformity. Project page. Slides.

Outcrops Gee Whiz

Thomas Martin (soon Colorado School of Mines), Zane Jobe (Colorado School of Mines), Fabien Laugier (Chevron), and Ross Meyer (Colorado School of Mines). The team wrote some programs to evaluate facies variability along drone-derived digital outcrop models. They did this by processing UAV point cloud data in Python and classified different rock facies using using weather profiles, local cliff face morphology, and rock colour variations as attributes. This research will help in the development drone assisted 3D scanning to automate facies boundaries mapping and rock characterization. Repo, Slides.

Jet Loggers

Eirik Larsen and Dimitrios Oikonomou (Earth Science Analytics), and Steve Purves (Euclidity). This team of European geoscientists, with their circadian clocks all out of whack, investigated if a language of stratigraphy can be extracted from the rock record and, if so, if it can be used as another tool for classifying rocks. They applied natural language processing (NLP) to an alphabetic encoding of well logs as a means to assist or augment the labour-intensive tasks of classifying stratigraphic units and picking tops. Slides.

Book Cliffs Bandits

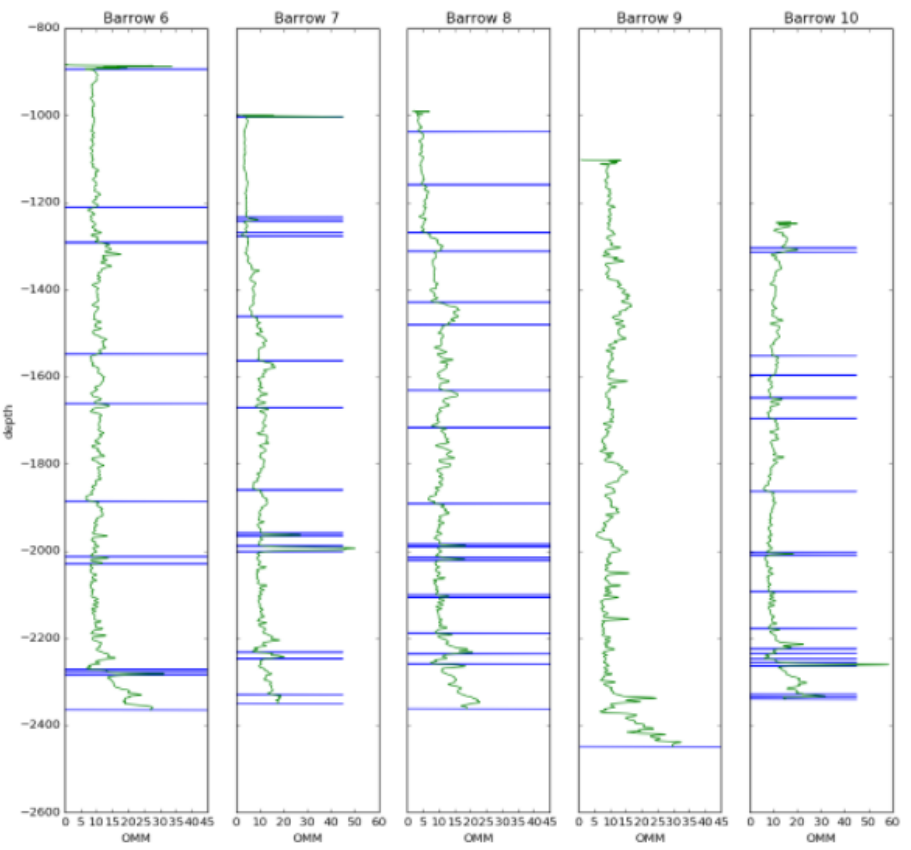

Tom Creech (ExxonMobil) and Jesse Pisel (Wyoming State Geological Survey). The team started munging datasets in the Book Cliffs. Unfortunately, they really did not have the perfect, ready to go data, and by the time they pivoted to some workable open data from Alaska, their team name had already became a thing. The goal was build a tool to assist with lithology and stratigraphic correlation. They settled on change-point detection using Bayesian statistics, which they were using to build richer feature sets to test if it could produce more robust automatic stratigraphic interpretation. Repo, and presentation.

A channel runs through it

Nam Pham (UT Austin), Graham Brew (Dynamic Graphics), Nathan Suurmeyer (Shell). Because morphologically realistic 3D synthetic seismic data is scarce, this team wrote a Python program that can take seismic horizon interpretations from real data, then construct richer training data sets for building an AI that can automatically delineate geological entities in the subsurface. The pixels enclosed by any two horizons are labelled with ones, pixels outside this region are labelled with zeros. This work was in support of Nam's thesis research which is using the SegNet architecture, and aims to extract not only major channel boundaries in seismic data, but also the internal channel structure and variability – details that many seismic interpreters, armed even with state-of-the art attribute toolboxes, would be unable to resolve. Project page, and code.

GeoHacker

Malcolm Gall (UK OGA), Brendon Hall and Ben Lasscock (Enthought). Innovation happens when hackers have the ability to try things... but they also need data to try things out on. There is a massive shortage of geoscience datasets that have been staged and curated for machine learning research. Team Geohacker's project wasn't a project per se, but a platform aimed at the sharing, distribution, and long-term stewardship of geoscience data benchmarks. The subsurface realm is swimming with disparate data types across a dizzying range of length scales, and indeed community efforts may be the only way to prove machine-learning's usefulness and keep the hype in check. A place where we can take geoscience data, and put it online in a ready-to-use for for machine learning. It's not only about being open, online and accessible. Good datasets, like good software, need to be hosted by individuals, properly documented, enriched with tutorials and getting-started guides, not to mention properly funded. Website.

Petrodict

Mark Mlella (Univ. Louisiana, Lafayette), Matthew Bauer (Anchutz Exploration), Charley Le (Shell), Thomas Nguyen (Devon). Petrodict is a machine-learning driven, cloud-based lithology prediction tool that takes petrophysics measurements (well logs) and gives back lithology. Users upload a triple combo log to the app, and the app returns that same log with with volumetric fractions for it's various lithologic or mineralogical constituents. For training, the team selected several dozen wells that had elemental capture spectroscopy (ECS) logs – a premium tool that is run only in a small fraction of wells – as well as triple combo measurements to build a model for predicting lithology. Repo.

Seismizor

George Hinkel, Vivek Patel, and Alex Waumann (all from University of Texas at Arlington). Earthquakes are hard. This team of computer science undergraduate students drove in from Texas to spend their weekend with all the other geo-enthusiasts. What problem in subsurface oil and gas did they identify as being important, interesting, and worthy of their relatively unvested attention? They took on the problem of induced seismicity. To test whether machine learning and analytics can be used to predict the likelihood that injected waste water from fracking will cause an earthquake like the ones that have been making news in Oklahoma. The majority of this team's time was spent doing what all good scientists do –understanding the physical system they were trying to investigate – unabashedly pulling a number of the more geomechanically inclined hackers from neighbouring teams and peppering them with questions. Induced seismicity is indeed a complex phenomenon, but George's realization that, "we massively overestimated the availability of data", struck a chord, I think, with the judges and the audience. Another systemic problem. The dynamic earth – incredible in its complexity and forces – coupled with the fascinating and politically charged technologies we use for drilling and fracking might be one of the hardest problems for machine learning to attack in the subsurface.

AAPG next year is in San Antonio. If it runs, the hackathon will be 18–19 of May. Mark your calendar and stay tuned!

Except where noted, this content is licensed

Except where noted, this content is licensed